Skyscraper, the Heterotopia par “Excellence”

After the end of America’s civil war in 1865 and the subsequent growth that followed, a range of tall, unfamiliar buildings gradually started to emerge in New York and Chicago’s high line. These buildings acted as promoters of the innovative applicable technologies of the time, while “manifesting the ambition and desire for power of self-begotten individuals.”[i] Fireproof steel-frame construction, the multiple amenities of electric lighting and the convenience of the elevator in commercially orientated buildings developed an aesthetic that is “consumable” in a different scale until today. Thus, “a new epoch began, that combined the end of the westward territorial expansion with an imperialist thrust overseas. The development of great steel and transportation companies gave rise to projects of unprecedented scale.”[ii] As of its town of origin at that point, “The Chicago Frame” acted as a spatial interpretation of the vast transformation Chicago and later NYC were undergoing during the end of the 19th century. This movement then, was not only for Chicago, but the United States in general, the pivot point for the frame construction in the process of “acquiring a significance which was less recognized.”[iii] It was “an expression of a technological sublime linked to the New World’s economic power.”[iv] Within this paper then, instead of simply analyzing the undeniable global/local relation of the skyscraper and its contribution in shaping America, I will try to introduce Foucault’s notion of counter spaces as a deriving agency of social structure and control, as a medium in forming the “New World” as it is now perceived.

Chicago, introduced its new building typology to the global public during the 1983 World’s Columbian Exposition. For a majority of people however, Chicago was not the monumental, yet ephemeral city its creators imagined, “but the ‘’black city’’ that had arisen since the great fire of 1871.”[v] According to Salivan, in Chicago, “the tall office building would seem to have arisen spontaneously, in response to favoring physical conditions, and the economic pressure as then sanctified, combined with the daring of promoters.”[vi] Bourget, a year after the fair, described these structures as “simple power of necessity is to a certain degree a principle of beauty; and these structures so plainly manifest this necessity that you feel a strange emotion in contemplating them. It is the first draught of a new sort of art – an art of democracy made by the mases and for the masses.”[vii]

Like doing so, many argued that this building typology which made its appearance in Chicago, the “cloud-presser” or as it is known today the “sky-scraper” “placed America in the forefront of architecture…the nation was at last more than a cultural colony of Europe.”[viii] However, not even a single deriving force from the reservoir of great architects desired to associate with such movement. Following great debates about this new kind of megastructure typologies and the impact they had for the city’s fabric, Chicago banned the construction of tall skyscrapers, passing the torch to New York City, commencing the battle of sky supremacy. There, not the exact same principles in terms of volume and mass were applied, however, purely rational construction was still the driving force regarding their design.

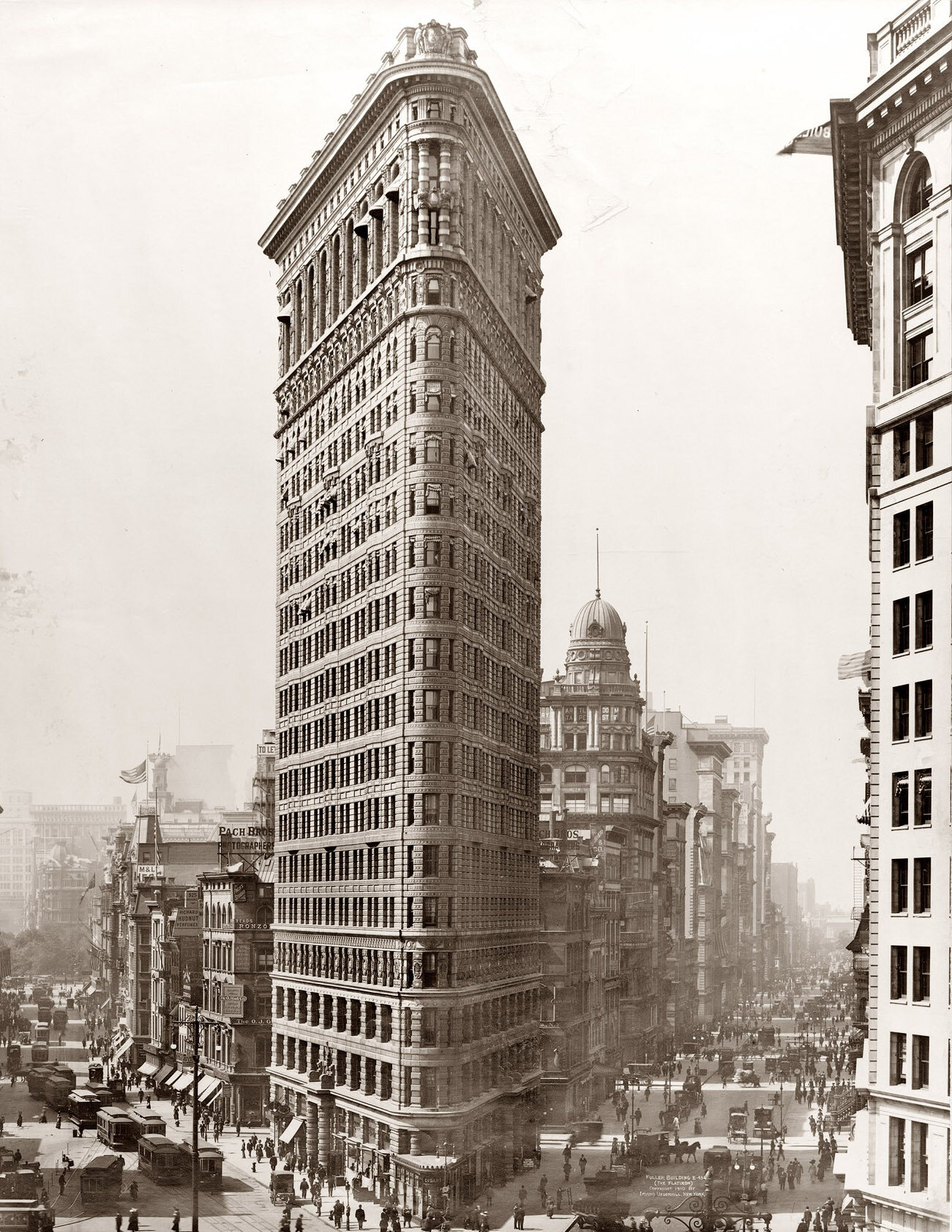

Looking at the concept of the skyscrapers through the prism of this first time period is fundamentally essential in understanding the basic principles in the process of utilizing the built environment as a manifestation of desire. However, personally, the true manifestation of its agenda could be more clearly seen in NYC and the Flatiron Building. It serve more than a single agenda, while at the same time acted as “a machine that makes the land pay.”[ix]

It is crucial at this point to understand the Flatiron Building not as one of the many skyscrapers of the 20th century, but the optimum celebration of the new world, a new America, built by men who had yet not long before acquired their new local continental identities. “The building embodied an architecture freed from many of the aesthetic restraints of the past. It was a building appropriate to a city upon which “the stamp of modernity was early put on”, as William Taylor notes, “by a succession of photographers and other graphic artists who were sensitive to the visual character that the city was assuming and who saw in these new shapes and forms a vision of the future.”[x]

That vision of the future however, started to unsettle the unified agency of the city, as it was perceived until the 20th century. It attained to cities like Chicago and New York a second identity or a second entity as in-between spaces within their own boundaries.. A city within a city, a series of barriers and separations, deriving from the idea of the center as a vast contiguous territory.[xi] It was “the passion to sell as an impelling force in American life.”[xii] It was about people’s obsession, Salivan’s included, to project the land-marking use of their buildings and the embedded, or rather not, qualities of architecture that they incorporated into their design. Prioritizing things like simplicity and height as a manifestation of their curriculum. As, according to Salivan, “it must be tall, every inch of it tall. The force and the power of altitude must be in it, the glory and pride of exaltation must be in it. It must be every inch a proud and soaring thing, rising in sheer exultation that from bottom to top it is a unit without a single dissenting line.”[xiii]

We must however acknowledge that the nonintegrated characteristics of the skyscraper gave birth to our contemporary notion of the metropolis and thus the modern global city, as it’s now perceived. “As man is a creature whose existence is dependent on differences, his mind is stimulated by the difference between present impressions and those which have preceded.”[xiv] Thus, the skyscraper was, and still is seen as a symbol, the most forceful manifestation of a culture that has turned away from all that is natural, simple and naïve.”[xv] “Aspects tight to this concept such as economic sustainability and money lure people with fraudulent inducements, only to corrupt and enervate them, to make them feeble, selfish and wicked.”[xvi] The skyscraper then, as an extension of the city that is located within acted not just as an expression of intent, but a public activity in theoretically combining the deviational elements of the city into a single image, a new reference point, “a unit, a thing with mind, with conscious purpose, seeing far in advance of the present and taking precautions for the future.”[xvii] It came to symbolize the material wealth of the individual, along with their capacity on forcefully manifesting their agenda on the surface of the city. Thus, marking the skyscraper, not just a mirror of man’s desire to ascend towards heaven, but also an implementing tool in manipulating communal spaces, by forcefully projecting its qualities upon them and consequently deriving social control.

Foucault, a French philosopher of the 20th century emphasized a lot of his studies around subjects like space, social structure and control. Foucault, in a lecture given to a group of architects in 1967, translated into English as “Of Other Spaces”, explicitly referred to a new way of spatial configuration, naming it heterotopia. There, he frames heterotopias as spaces in which an alternative social ordering is performed, spaces in which a new way of ordering emerges that stands in contrast to the taken-for-granted mundane idea of social order that existed within society at that time.[xviii] For Foucault, space has the symbolic notion of holding a reserve of actions. Thus, by using the skyscraper in the process of unfolding Foucault’s notion about space and freedom, this megastructure can indeed be seen as such a place. “A place of “otherness”, whose existence sets up unsettling juxtapositions of incommensurate “objects” that challenge the way we think, especially the way our thinking is ordered.”[xix] . That semi-real society which was formed around the skyscraper and birched the reincorporation of people to their socially structured everyday life, can be contextualized in its most appropriate way using Foucault’s notion of heterotopia. “Exposing that, even within them, there is a mirror image of society.”[xx]

No one can deny the utopic characteristics of the skyscraper during the 19th century and implementing Foucault’s notion about the in-between spaces, the emergence of these alternative counter sites that he names heterotopias. For Foucault, “between utopias and these quite other sites, these heterotopias, there might be a sort of mixed, joint experience, which would be the mirror. The mirror is, after all, a utopia, since it is a placeless place. In the mirror, I see myself there where I am not, in an unreal, virtual space that opens up behind the surface. But it is also a heterotopia in so far as the mirror does exist in reality, where it exerts a sort of counteraction on the position that I occupy. It makes this place that I occupy at the moment when I look at myself in the glass at once absolutely real, connected with all the space that surrounds it, and absolutely unreal, since in order to be perceived, it has to pass through this virtual point which is over there.”[xxi]

By unraveling Foucault’s notion then, the skyscrapers as an entity could and should be seen as a heterogeneous juncture that mixed up opposite qualities and ideals in complex ways. It is useful as a “modeling” of something that is both ”critical and utopian for the time: a place that is different or pleasurable for some, as well as representing a communal ideal,” or an ideal desire I might add.[xxii] The skyscraper then acted as an obligatory point of passage constituted through different ordering practices that made visible, if only for a short time, conditions of difference that opened up a new perspective on the old order and all its faults.[xxiii] Chicago and NYC did seem to experience a prevision of two of the major themes of twentieth century architecture – “the frame structure and the composition of intersecting planes.”[xxiv] However, we must not forget that the skyscraper of the 19th and early 20th century failed to acknowledge the underline desires of its inhabitants, proven by the few remaining structures in both cities, by “selling” a vision without action for some, or an action without vision for others. That been said, we can’t undermine the significance of this new building typology merging fragments of the past and future technology, synthesizing an interdisciplinary agenda that is still prominent today.

[i] Wolner, Edward W. “The City-within-a-City and Skyscraper Patronage in the 1920's.” Journal of Architectural Education (1984-), vol. 42, no. 2, 1989, p.10.

[ii] Cohen, J.L. The Future of Architecture since 1889. Phaidon, London, 2012, p.55.

[iii] Rowe, C. “The Chicago Frame” (1956), The Mathematics of the Ideal Villa. MIT, 1976, p.90.

[iv] Cohen, J.L. The Future of Architecture since 1889. Phaidon, London, 2012, p.55.

[v] Cohen, J.L. The Future of Architecture since 1889. Phaidon, London, 2012, p.56.

[vi] Sullivan, L. “Retrospect,” The Autobiography of an Idea, 1924. Dover, 1956, p.314.

[vii] Cohen, J.L. The Future of Architecture since 1889. Phaidon, London, 2012, p.58.

[viii] Flowers, B. Skyscraper: The Politics and Power of Building New York City in the Twentieth Century. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009, p.16.

[ix] Flowers, B. Skyscraper: The Politics and Power of Building New York City in the Twentieth Century. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009, p.15.

[x] Flowers, B. Skyscraper: The Politics and Power of Building New York City in the Twentieth Century. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009, p.15.

[xi] Sullivan, L. “Retrospect,” The Autobiography of an Idea, 1924. Dover, 1956, p.305.

[xii] Sullivan, L. “Retrospect,” The Autobiography of an Idea, 1924. Dover, 1956, p.312.

[xiii] Cohen, J.L. The Future of Architecture since 1889. Phaidon, London, 2012, p.57.

[xiv] Simmel, G. “The Metropolis and Mental Life” (1903), from On Individuality and Social Forms, ed. Donald N. Levine, University of Chicago, 1971, p.325.

[xv] August Endell. Excerpts from The Beauty of the Great City (1908), Iain Boyd Whyte and David Frisby, eds., Metropolis Berlin, 1880–1940, University of California, 2012, p.36.

[xvi] August Endell. Excerpts from The Beauty of the Great City (1908), Iain Boyd Whyte and David Frisby, eds., Metropolis Berlin, 1880–1940, University of California, 2012, p.36.

[xvii] Rodgers, T.D. “Civic Ambitions,” from Atlantic Crossings: Social Politics in a Progressive Age, Harvard, 1998, p.160.

[xviii] Foucault, M. “Of Other Spaces”, translated by Jay Miskowiec, Architecture/Mouvement/Continuité, 1984.

[xix] Foucault, M. “The Order of Things”. Routledge London, 1989.

[xx] Stallybras, P. & White, A. The Politics and Poetics of Transgression, Cornell University Press Ithaca, New York, 1986, p.18.

[xxi] Foucault, M. “Of Other Spaces”, translated by Jay Miskowiec, Architecture/Mouvement/Continuité, 1984.

[xxii] Lefebvre, R. The Urban Revolution. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 2003, p.125.

[xxiii] Foucault, M. “The Order of Things”. Routledge London, 1989.

[xxiv] Rowe, C. “The Chicago Frame” (1956), The Mathematics of the Ideal Villa. MIT, 1976, p.92.

Bibliography

· Cohen, J.L. The Future of Architecture since 1889. Phaidon, London, 2012. [Secondary]

Within this book, Jean – Louis Cohen Explains how America was rediscovered architecturally through the skyscraper, while at the same time justifying why great architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright did not involve in the process.

· Deamer, P. Architecture and Capitalism. Routledge, New York, 2014. [Secondary]

Architecture and Capitalism focuses on the relationship between money (economy) and architecture spanning from the mid-19th century(the birth of the skyscraper) till today, contextualizing the overall evolution of this megastructure.

· August Endell. Excerpts from The Beauty of the Great City (1908), Iain Boyd Whyte and David Frisby, eds., Metropolis Berlin, 1880–1940, University of California, 2012, 35–41, 122–24 [Primary]

Despite Endell focusing in the concept of the metropolis and Berlin, his text is a great contribution towards aesthetic theory, encouraging people to free themselves from “the here and the now.”

· Flowers, B. Skyscraper: The Politics and Power of Building New York City in the Twentieth Century. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009. [Secondary]

In the first chapter of this book, building, power and money, the author, while emphasizing in New York City, deconstructs the concept of the skyscraper as the sum of the inputs towards its implementation.

· Foucault, M. “Of Other Spaces”, translated by Jay Miskowiec, Architecture/Mouvement/Continuité, 1984. [Secondary]

Foucault in this speech he gave in 1967 introduced a new type of space, Heterotopias. He defined such spaces as ones that have more layers of meaning in relation to other spaces, using the example of the mirror.

· Foucault, M. “The Order of Things”. Routledge London, 1989. [Secondary]

Within his text, Foucault is describing certain periods of history through literature, art and economy opening the path to a whole new way of critical thinking.

· Lefebvre, R. The Urban Revolution. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 2003. [Secondary]

The Urban Revolution is one of Lefebvre’s initial critiques on urban societies highlighting the urban dimensions of modern life.

· Rodgers, T.D. “Civic Ambitions,” from Atlantic Crossings: Social Politics in a Progressive Age, Harvard, 1998, 160–81 [Secondary]

Within his text, Rodgers talks about Capitalism, modernist architecture – city planning as well as reconstructing the new great city.

· Rowe, C. “The Chicago Frame” (1956), The Mathematics of the Ideal Villa. MIT, 1976, p.89–109[Secondary]

Within his text, Rowe elaborates in the subject of the Chicago frame, Salivan and the significance of the structure in the progression and implementation of the skyscraper.

· Simmel, G. “The Metropolis and Mental Life” (1903), from On Individuality and Social Forms, ed. Donald N. Levine, University of Chicago, 1971, 324–39 [Primary]

Although this text does not emphasize solely in the concept of the skyscraper, it’s a valuable resource in understanding the greater scale – the city- within which the skyscraper evolved to be an integrated characteristic.

· Stallybras, P. & White, A. The Politics and Poetics of Transgression, Cornell University Press Ithaca, New York, 1986. [Secondary]

Stallybras and White within their text are referring to the formation of the Western Societies by comparing multiple discourses in a variery of domains.

· Sullivan, L. “Retrospect,” The Autobiography of an Idea, 1924. Dover, 1956, p.304–30[Primary]

Sulivan’s autobiography of an idea is a great resource indicating not just the evolution of the Chicago movement but also the perspective of an individual who was directly involved within the movement.

· Willis, C. Form Follows Finance, Princeton Architectural Press, New York, 1995. [Secondary]

Willis in his book ‘Form Follows Finance’ introduces the main characteristic of the difference between the Chicago and New York skyscraper as the outcome of different economic conditions and the need to fulfil certain desires.

· Wolner, Edward W. “The City-within-a-City and Skyscraper Patronage in the 1920's.” Journal of Architectural Education (1984-), vol. 42, no. 2, 1989, p. 10–23 [Secondary]

Despite refereeing to the 20’s Wolner makes a very good analysis in the effect of separation and division that the skyscraper introduced to the uniform city as it was till then perceived.