The Reticent of the Outside

Since its very beginning architecture has always been a profession interested in pursuing what is beyond, what we can’t grasp, while at the same time, informing and being informed by the tension between possibilities along the way. From the 18th century and Piranesi, this out of the box emerging ideas did not only shape the way we are practicing architecture today, but shaped our dogma, our approach towards the challenges that we set out to deal with. Thus, the true manifestation of the way we are practicing architecture could be interpreted in Fuller’s phrase “Often I found where I should be going only by setting out for somewhere else.”[1]

“Architects should think about the body within an interior in the same way that they imagine it within the environment.”[2] The rigid architectural qualities of the past did not question such assumptions, limiting the capacity of the house to act as just a box. That “completeness” of the box, interpreted today as a compromise towards a familiar form, shaped our societies till the beginning of the 20th century. “Breaking the box” hence, extended not only the house but also the authority and responsibility of the designer.”[3]

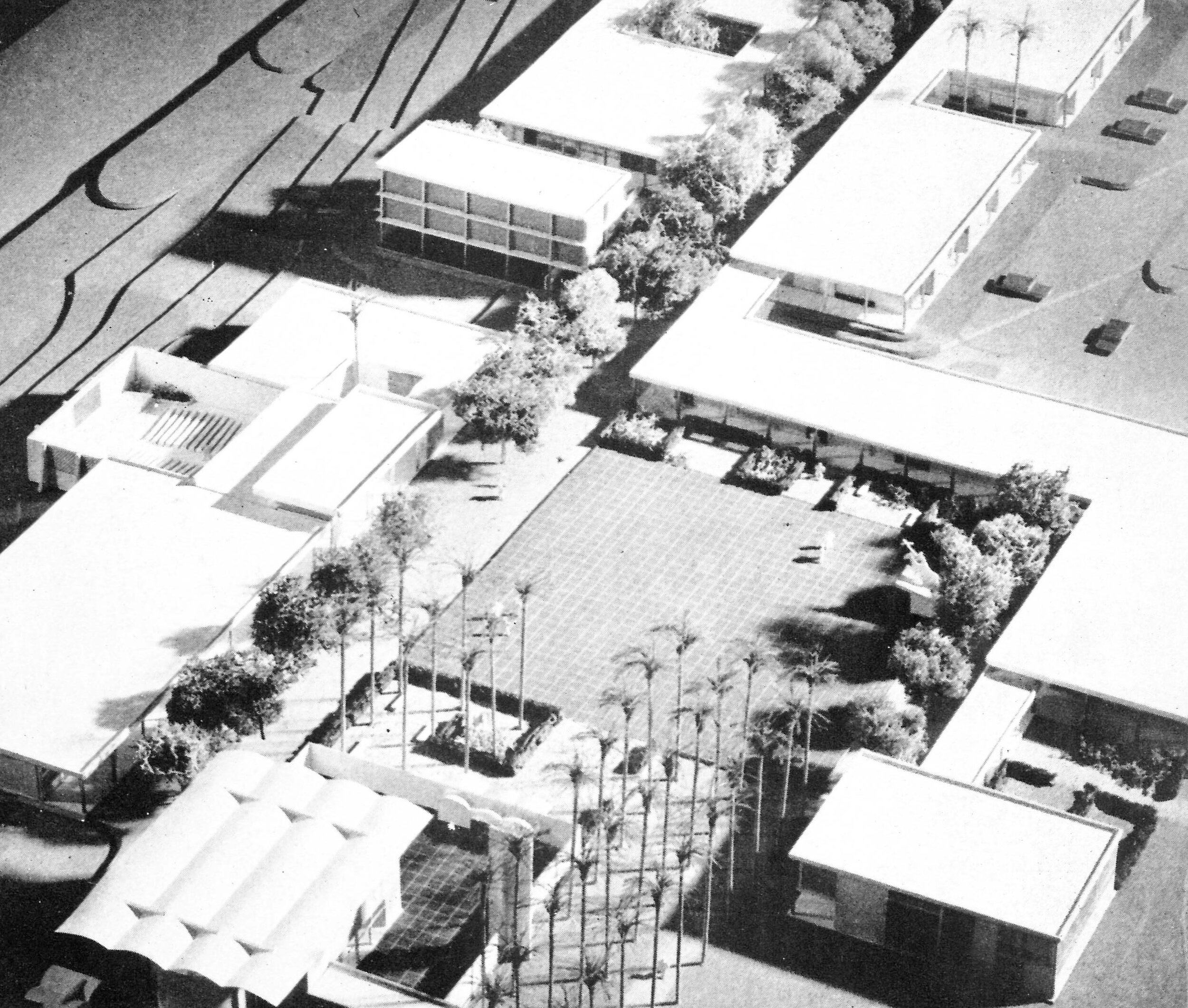

Greece, as a country which has implemented the basic patio idea, despite an initial discrepancy presented in each city’s site plan and hence a prothesis to interpret each of these inputs as different entities, all of the cities use the patio as a trademark. Visible in a whole range of scales, homogenizing the part to the whole, creating a series of hybridized assemblage spaces for both the public, the primate and the in-between.[4] Over the years, many argued that “the atmosphere of the open country encourages centrifugal habits – people going away from each other rather than getting to know each other better.”[5] However, that couldn’t be furthest from the truth. If “the building’s site plan, section, and construction details were developed in dialogue with its ambient circumstances,”[6] then the “outdoor living rooms must be created on every level – for the smallest family unit, for each block and neighborhood. For the city as a whole.”[7]

According to Loos, ”The house should be reticent on the outside and unveil its entire richness on the inside.”[8] That ‘traditional’ way of informing our dwellings, in the beginning of the 20th century came in contrast with the work of architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright. His and many other designs, focused towards a form of compositional synthesis, images of functionality, moving away from the strict notion of the house and its privacy as was yet perceived by the bourgeoisie. In agreement with Wright’s design logic, “the living room, where one can live and think freely, is neither attractive nor harmonic nor photogenic; it came about as the result of accidental events, which will never be finished, and by itself can absorb anything whatsoever to satisfy the owner’s varying expectations.”[9]

If site and program act as design inclinations, then “anyone who has the desire to rest his posterior on a rectangle is in the depth of his soul filled with totalitarian tendencies.”[10] Many architects tried to invoke the sense of the organic within the concept of the patio and thus integrate a plethora of diverse and unique qualities into our everyday lives. Each of these qualities however, “traces aspects of typical situations that are dependent on others, no matter whether the dependency is approximate sameness or difference, gradation or contrast.”[11] As a result, we will always struggle to inform our enclosed openness, but very openness , or the lack of it, won’t strife to inform us.

[1] Blauvelt, Andrew, Greg Castillo, and Esther Choi. Hippie Modernism the Struggle for Utopia. Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2015, p.73

[2] David Leatherbarrow, “Sitting in the City,” Architecture Oriented Otherwise (New York: Princeton Architectural Press), 143.

[3] David Leatherbarrow, “Sitting in the City,” Architecture Oriented Otherwise (New York: Princeton Architectural Press), 171.

[4] J. L. Sert, “Can Patios Make Cities,” Architectural Forum, (August, 1953), 124.

[5] J. L. Sert, “Can Patios Make Cities,” Architectural Forum, (August, 1953), 128.

[6] David Leatherbarrow, “Sitting in the City,” Architecture Oriented Otherwise (New York: Princeton Architectural Press), 156.

[7] J. L. Sert, “Can Patios Make Cities,” Architectural Forum, (August, 1953), 124.

[8] David Leatherbarrow, “Sitting in the City,” Architecture Oriented Otherwise (New York: Princeton Architectural Press), 155.

[9] David Leatherbarrow, “Sitting in the City,” Architecture Oriented Otherwise (New York: Princeton Architectural Press), 160.

[10] David Leatherbarrow, “Sitting in the City,” Architecture Oriented Otherwise (New York: Princeton Architectural Press), 159.

[11] David Leatherbarrow, “Sitting in the City,” Architecture Oriented Otherwise (New York: Princeton Architectural Press), 171.