The Heretic Dogma of the Machine

· If a machine has the capacity to produce the space within we live in, do we want the machine’s limitation to govern our everyday place?

· To what extend the lack of dogma across the profession led to the “invasion” of more valid socially defined professions?

What is architecture? What is the role of the architect within the society? Is architecture an artistic depiction at the scale of a building or is it the sum of researched quantifiable inputs? The nature of the architect is always to challenge the fundamental assumptions of any given moment. During the 1960’s a new medium for the implementation of such challenge evolved, the computer. For some, the computer was a new platform for advancing the design capabilities of the time, were for others it acted as an isolation from the organic methodologies of the past. That been said, we must not forget that “by itself, the computer in architectural design is as much, and as little, a tool as a tee-square, a drafting machine, or a slide rule. The real difference lies in the fact that the computer leads us to think much more rigorously about what we are up to than those other aids ever demanded.”[1]

Perhaps, the most challenging aspect of the computer was its very own input and output nature. Approaching architecture through the medium of such machine required a logic that was only possessed by its “native” users. If we look at the role of the computer in architecture nowadays, we can clearly identify its significant as a conceptual tool which, at the same time, has the capacity of analysis. The pioneer platform of the computer in architecture then, exposed architecture as a profession that lacked a logic to call its own, the scientific knowledge of “input”, and hence making their output an accumulation of superfluous aesthetics.

” In the work of the Cambridge methodologists, texts, formulae, diagrams, and computer code replaced plans, elevations, and photographs as the proper tools of architectural research, and the long-held understanding of the building as an object of sensory engagement was replaced by the idea of the building as a system of functional relationships.”[2]

Many opposed at the idea of the machine/scientist taking over the role of the architect and shaping the built environment. For them, such machines were just an interpretation of algorithms that lacked the past experiences of an architect combined with his aspiration for the future. There is no denial that during this post war standardized period, the computer acted as an opportunity in the process of developing mathematically based theories of architecture that could set up a framework for entire building or even cities. There is also no denial about the fact that despite the machine’s ability to test thousands of possibilities, such tests came to the expense of time.

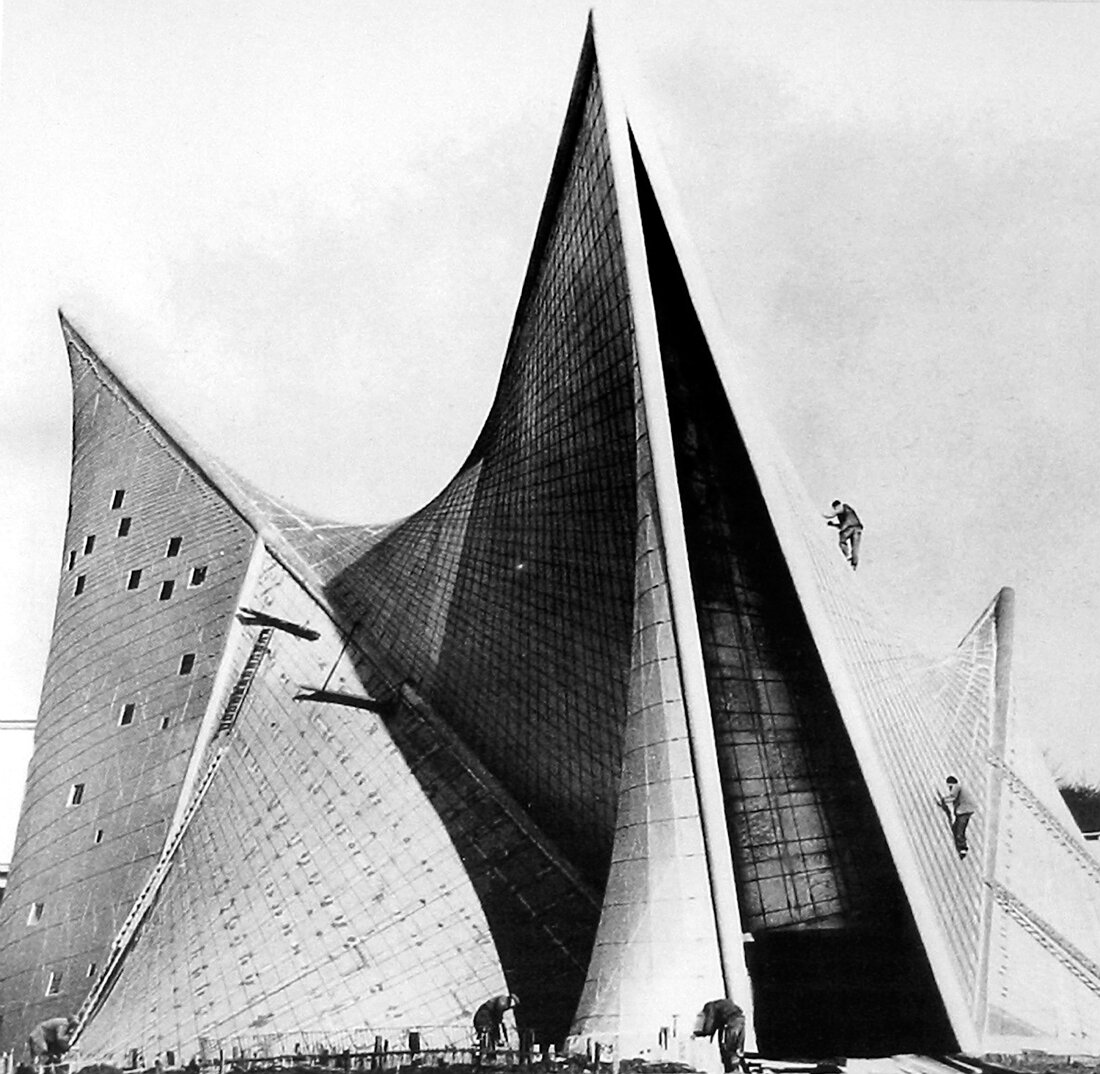

By all means the aspiration of “prefabricating” the means by which we practice architecture was something very ambitious. The application of the most appropriate algorithms to different sets of building requirements however can’t produce the “ideal” architecture form. There is no need to highlight the significance of the computer in the profession during the 21st century, as the tools it has given us revolutionized not only the way we live, but also the way our living is ordered. Many argued about the threat of the machine in the organic process of conceptualizing architecture and the limitations such mediums may cause. But we must never forget the very input output nature of such machines. Algorithms were used to design a buildings’ specific adjacency requirements, but the very own algorithms were used to design the Philips Pavilion.

[1] Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Seagram Building, New York, 1958. P.42

[2] Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Seagram Building, New York, 1958. P.51-52