The House As The Foundation Of Our Structured Everyday

· Is prefabrication an ally of the architect or a limitation of his design work?

· To what extend did we shape our houses and our houses shaped our everyday lives?

A house is “a building for human habitation, especially one that is lived in by a family or small group of people.”[1] “It is the basic instrument of living within our own time; a solution of human need for shelter that is structurally contemporary.[2] However, “the reality of the building does not consist of walls and roof but space within to be lived in.”[3] if we look back at the evolution of the house during the past century, it is clear that this development was not based upon a linear timeline of progression.

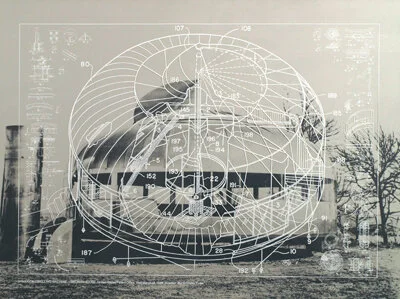

The concept of the house is key in the process of understanding why our cities look like they do , and why our modern perception of life was contested and contrasted upon the given principles. For the majority of the world, the house besides shelter stood as a status symbol within each society. It was the contextualization of the evolution of the machine that made gradually visible the capacity of the machine and its opportunity to contribute towards a new way of living.

Man’s growing awareness of his real powers and his true capabilities came through the machine.[4] It helped nations to win wars and rapidly change not only the way we live but also the way our living is ordered. It formed cities while at the same time enabled one of the most fascinating for me parts of the city, the suburbs. It provided people the opportunity of a “better way of life” while at the same time being part of the larger conceptual body of the city. My goal however is not to project the suburb as a “relationship of rupture and denial with the rest of the city”.[5] Rather, I wanted to highlight the capacity of the machine to extend our way of living beyond the static, as it was until then perceived, boundaries of the city.

Inevitably however, the machine did not have only a positive contribution in the process of shaping our contemporary notion of the house. “The laboratory might had been put on the production line”[6] but the concept of mass production associated not only the aesthetics of the house but its core principles as well. As a result, the machine made possible, in a short amount of time, the implementation of a better way of living for some, while for others, it acted as the catalyst in duplicating the same prefabricated model around vast unrelated territorial expansions.

So, to what extend did we shape our houses and to what extend did our houses shape us? That is the question we have to ask ourselves in order to truly determine the contribution of the machine towards the life in the 21st century. Within this report, by no means I tried to undermine the significance of the machine in the process of industrializing systems of prefabrication. My main concerns was how much did those systems shaped our contemporary identities and to what extend are we a product of our own “human prefabrication”

[1] https://www.google.com/webhp?sourceid=chrome-instant&ion=1&espv=2&ie=UTF-8#q=house+definition

[2] J. Entenza, et al. “What is a House?” in Arts and Architecture vol. 61, no. 7 (1944): 5

[3] F. L. Wright. “Organic Architecture” (1939) in Frank Lloyd Wright: Collected Writings, Volume 3:

1931-1939, ed. Pfieffer. New York: Rizzoli, 1994: 303.

[4] J. Entenza, et al. “What is a House?” in Arts and Architecture vol. 61, no. 7 (1944): 8

[5] L. A. Herzog. “Barra da Tijuca: The Political Economy of a Global Suburb in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil” in

Latin American Perspectives vol. 40, no. 2 (March 2013): 121

[6] J. Entenza, et al. “What is a House?” in Arts and Architecture vol. 61, no. 7 (1944): 12