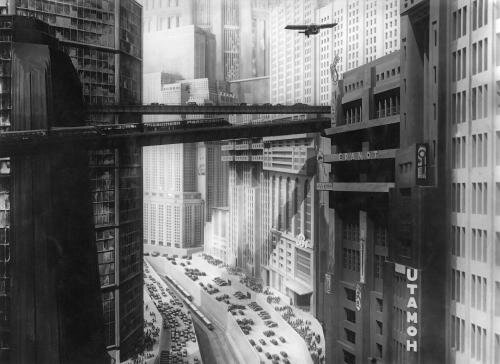

Metropolis, The Dystopic Utopia We Call Home

According to the Cambridge dictionary, metropolis is the capital or chief city of a country or region. A very large and densely populated industrial and commercial city.[i] Metropolis, has been a point of conflict among scholars since its formation. From Nietzsche to Charles Booth, a wide range of viewpoints emphasizing on the investigation of the relationship which the social structure of the metropolis promoted between the individual aspects of life and those which transcend the existence of single individuals is still a point of departure for many current debates.[ii] For a majority of critics, the metropolis, the great city, has always been the target of intemperate denunciation. It was, and still is seen as a symbol, the most forceful manifestation of a culture that has turned away from all that is natural, simple and naïve.[iii] For them, aspects tight to the concept of metropolis such as economic sustainability and money lure people with fraudulent inducements, only to corrupt and enervate them, to make them feeble, selfish and wicked.[iv]

For others however, the metropolis was an image, an expression of intense, public activity and a picture in the mind. Frederic Howe, further articulates his architectonic concept of metropolis by describing it as a unit, a thing with mind, with conscious purpose, seeing far in advance of the present and taking precautions for the future.[v] He refused to engage in the fundamental motive of the time regarding the resistance of the individual to being levelled, swallowed up in the social-technological mechanism.[vi] Equally, he believed that through public design, the core values of a society could and should be written in its street design and public buildings, its shelters and its cityscapes.[vii]

On the other hand, we have to admit that life in the context of the metropolis is stressful and thus unhealthier than the more rural alternatives. The city inhabitants are becoming more and more detached from nature and hence many could argue from many opportunities of happiness. But, the astonishing thing is, the metropolis, for all its ugly buildings, its noise, its manifold shortcomings-is a miracle of beauty and poetry: a fairy tale more colorful, more prolific, than any told by a poet. This may sound like paradox, but anyone who is not blinded will soon enough perceive that its streets contain a thousand beauties, countless wonders, infinite riches, spread out before our very eyes and yet seen by so few.[viii]

As man is a creature whose existence is dependent on differences, his mind is stimulated by the difference between present impressions and those which have preceded.[ix] Hence, we experience change through the daily scene; but there are some rarely visited places that leave specific impressions, whether of charm or of grandeur, etched in the memory.[x] The concept of metropolis offered just that. It formed the basis upon which the vision of a community that could stretch beyond the “ownership” of its own basic infrastructure would resolve in the process of shaping and implementing its own design. It was a form of hybrid spatial formation as a function of travel and the growing needs of an expanding community, allowing each city to acquire its own distinctive pattern and form.

Property, law and politics are for some the three elements that profoundly shaped the metropolises’ outer form. Even if this is the case, the “occupancy” of the inner skin of the city it still an aspect subject to its inhabitants. Even the most strictly defined and designed spaces can acquire a different identity due to their inhabitant’s qualities. Over the years, a lot have been said about the faceless place called metropolis and the blasé attitude of their inhabitants. There is however something that made these cities stand and evolve through the years. Personally, I believe it was the diversity of an aggregate of people (the inhabitants) creating an active group of people who had the capacity to see the metropolis as a process rather than a city and thus, were able to apply an extra layer of meaning on top of their strictly defined urban context. They were capable to see a “wall” as something more. As something alive that changes and evolves along them. As something that changes into a gray, monotonous solid object during the foggy days, like they did. As something full of life and movement during a sunny day, like they were. Thus, looking back at the early stages of the metropolis, the question that arises is what can we learn from the past to inform our future?

[i] http://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/metropolis

[ii] Georg Simmel, “The Metropolis and Mental Life” (1903), from On Individuality and Social Forms, ed. Donald N. Levine (University of Chicago, 1971), p.325

[iii] August Endell, excerpts from The Beauty of the Great City (1908), from Iain Boyd Whyte and David Frisby, eds., Metropolis Berlin, 1880–1940 (University of California, 2012), p.36

[iv] August Endell, excerpts from The Beauty of the Great City (1908), from Iain Boyd Whyte and David Frisby, eds., Metropolis Berlin, 1880–1940 (University of California, 2012), p.36

[v] Daniel T. Rodgers, Atlantic Crossings, The Belknap Press of Harvard Univeristy Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England, 1998, p.160

[vi] Georg Simmel, “The Metropolis and Mental Life” (1903), from On Individuality and Social Forms, ed. Donald N. Levine (University of Chicago, 1971), p.324

[vii] Daniel T. Rodgers, Atlantic Crossings, The Belknap Press of Harvard Univeristy Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England, 1998, p.161

[viii] August Endell, excerpts from The Beauty of the Great City (1908), from Iain Boyd Whyte and David Frisby, eds., Metropolis Berlin, 1880–1940 (University of California, 2012), p.36

[ix] Georg Simmel, “The Metropolis and Mental Life” (1903), from On Individuality and Social Forms, ed. Donald N. Levine (University of Chicago, 1971), p.325

[x] August Endell, excerpts from The Beauty of the Great City (1908), from Iain Boyd Whyte and David Frisby, eds., Metropolis Berlin, 1880–1940 (University of California, 2012), p.123