Dystopian Realities, Utopian Ideals

Auroville as the Foucauldian “Pirate Island” of the Twentieth Century

Introduction:

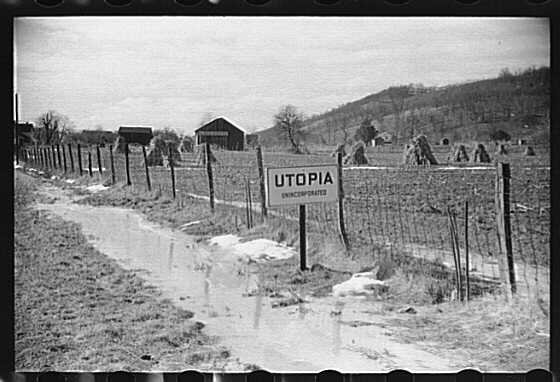

The idea of the utopian community always has an element of fascination within existing societies due to their radically imposed importance of the individual as an alternative way of communal creation. “Such communities are mainly based on principles of equality in economics, justice, and law implementation, promoting not only the principles of the individual but the communal ideal of the majority.”[1] In 1968, a utopian community in India, better known as Auroville, was built. [Figure 1] Auroville was designed as a multicultural community which not only accepted the diversity of its inhabitants, but, at the same time radically imposed its own new rules[2]. Over the centuries, many different examples of such communities prominently emerged and then disappeared due to an embodied clash within their members. From the 19th century, numerous utopian communities started to loom all over America like New Harmony in Indiana. Notwithstanding the test of time, it collapsed five years after its formation due to its member inability to self-sustain. Auroville however, is different not only because of the architectural language it used to promote its ethos, but also for eliminating the segregating characteristic of human nature such as money or religion towards the uniformity of the whole.

Within this paper, Auroville will be used as a case study in the process of unraveling the characteristic of such utopic communities, and through Foucault’s notion of utopic-heterotopic space, it will act as a base upon which arguments about its succession, or partial debacle, will be contested and contrasted.

Theoretical Framework: Foucault’s Pirate Ship

To fully exploit the idea of utopia, and the importance of projects such as Auroville it is imperative to establish a theoretical framework through which an argument about Auroville’s success, or rather not, could emerge. Michel Foucault’s theories on utopias and dystopias serve as an ideal framework. In 1966 in a lecture given to a group of architecture students translated to English as” Of Other Spaces,” Foucault finished his speech with the phrase: “The ship is the heterotopia par excellence. In civilizations without boats, dreams dry up, espionage takes the place of adventure, and the police take the place of pirates.”[3] By no means does Foucault equating the police with the pirates; however, by comparing the two, he is highlighting the necessity of such modes of ordering to operate within a strict framework, which sometimes may even resemblance the police. Pirates cannot be pirates without a sword or a ship. They can not exist without a strict structure within their society. His intention then is not trying to romanticize them, rather, he is showing that within them there is a mirrored image of the society.

“After Foucault first utilized the term heterotopia, the word was used either directly or sometimes to define marginal space, paradoxical space or counter-sites.”[4]However, for the purpose of this paper, six ways are most prevailing in describing such spaces.

• “As sites that are constituted as incongruous, or paradoxical, through socially transgressive practices.”[5]

• “As sites that are ambivalent and uncertain because of the multiplicity of social meanings that are attached to them, often where the meaning of a site has changed or is openly contested.”[6]

• “As sites that have some aura of mystery, danger or transgression about them; places on the margin perhaps.”[7]

• “Sites that are defined by their absolute perfection, surrounded by spaces that are not so clearly defined as such.”[8]

• “Sites that are marginalized within the dominant social spatialization.”[9]

• “Incongruous forms of writing and text that challenge and make impossible discursive statements.”[10]

However, in defining heterotopias as spaces of an alternative ordering, it is crucial to understand that ordering is not just about fixing things in an established way so that things make sense, it is principally about ways in which social activities are arranged and distributed in relation to the contingent effect of those arrangements. Such issues will be discussed in the coming chapters, using Auroville as a spatial “tale”, a mean of their articulation.

Historical Context

The desire for utopic communities however, is not just some opposing desire to the expanding web of the modern city. Human nature always leads people to question fundamental assumption of each era, thus alternative ways of communal ordering emerged. Those orderings vary from the collective formations of the first cave dwellers to the disjointed proposal of the 21st century “House for Doing Nothing” by Aristede Antonas. [Figure2] Despite their totalitarian schism however, all of these alternatives reject the stiff, taken for granted principles around which our societies are made, and proposed alternative ways of assembly. The operation of such enclosed clusters captures, and more importantly manifests, the aspirations behind their implementation which can be routed back to the ancient Greeks. This however does not refer to the formation of the initial exchange based communities, but rather the utopian alternative approaches that were proposed long after the “dystopic” notion of religion, money or slavery had been associated with such populated clusters. “The first documented utopian proposal dates back to Plato’s republic.”[11] [Figure 2] Plato, radically proposed a total reorganization of the community, changing fundamental assumptions upon which it was until then constructed, enabling this new hybrid of specializations to achieve every implementation of a common desire. He categorized citizen into three socioeconomic classes: gold, silver and bronze.[12] Each class would have certain responsibilities directly tied to their skills within the society, helping the community to strive for the security and freedom such societies were lacking at the time. The integration of the population in those three groups was solely based on their level of education and thus their ability to afford it, inevitably introducing an even greater spatial dysfunction or even segregation within the existing community web.

Plato’s notion of utopia then was a series of cluster within the existing city fabric that allow society to flourish without intervening with its surrounding build environment. However, the idea of the form as a container of such utopic endeavors had always had an element of fascination for a great number of scholars over the centuries. Why does our notion of Utopia always look so futuristic? And in turn, does that render our capacity to fully grasp it so far-removed from our current abilities? Many scholars can argue that such concepts only exist as a projection of social concern. Buckminster’s Fuller Geodestic dome covering Manhattan or Superstudio’s “Continuous Monument” however do not simply highlight that. They highlight the capacity of the individual, and society’s as an extension, that is needed to reach the qualities of what cannot be perceived: utopia itself. Instead of looking such projects from the scope of the unperceived, they should be seen as “heterogeneous junctures that mixed up opposites in complex ways. They are useful as a ‘modeling’ of something that is both utopian and critical: a place that is different and even pleasurable, as well as representing a communal ideal, or an ideal desire.[13] Their scale and the extent of their programmatic function presupposes full attribution of responsibility as vital component toward their successive implementation. Hence, there is a reason why the unperceived is always formed in this “non consumable”, out of reach scale and why existing societies that endure until now will never be able to adopt to it. By creating the ideal framework for a community to thrive, one has to fully accept the importance of his actions. Despite the diversity of such projects in addressing the pressing needs of each era, they share a common ground. The evolving input is still the individual.

A Community’s Architecture from a Different Perspective

Both Archigram’s notion of settlement and Constantinos Doxiadis’s city of tomorrow, despite projecting a diverse approach compared to Auroville, hold significant importance in understanding the idealistic framework of habitation that we are still yet to enact in our present cities and communities. Both tried to create a system and a way of scientifically defining human settlement by interpreting it as a well thought intuitive process rather than the gradual unplanned expansion taking place until today. Their endeavor did not presuppose an emphasis on the people, but rather the optimum. Archigram’s project introduce a notion of necessary temporality within our surroundings which until then we lacked. “The Walking City” [Figure 6], redefined the urban, by questioning and boldly reversing the role of infrastructure within a city. It exploited the idea of the framework as something more than just a supporting layer in the existing city fabric. Rather, Archigram’s notion of a habitable infrastructure fully exploited the capacity of a community to exploit its resources at any given moment. “Ecumenopolis” on the other hand [Figure 7], embraced the expansion of the city as an accommodation of technological evolution, setting the stepping stone of settlement needs within the wider context of the world. Its aim was to blur the boundaries between the local and the global, reinventing the world in the year 1967. [14]

The lack of implementation of both projects does not render them ineffectual; rather, the provocation of the “Walking City” redefines our notion of a city as an evolving “organism”, while “Ecumenopolis” “highlight[s] the importance of optimizing a man’s relationship with his environment.”[15] Hence, they provide a diverse basis, an alternative way of defining the idea of the city and settlement, upon which Auroville could be contested and contrasted as a human-made system. Thus, interpreting these new ways of doing architecture as something more than alternatives from the past. Precedents for future approaches.

Auroville as a Prominent Influence of Utopic Communities

Auroville is an experimental city located in the district of Tamil Nadu in India.[Figure 8] It was founded in 1968 by Mirra Alfassa and designed by Roger Anger.[16] “Auroville is a universal town where men and women of all countries are able to live in peace and progressive harmony, above all creeds, all politics and all nationalities. The purpose of Auroville is to realize human unity.”[17] That manifesto was the driving force behind the planning and construction of the city. Numerous cities before or after Auroville tried to expand on the idea of the utopic city but none ever achieved such a diverse body of residences. It was designed, and still remains, as a diverse populated enclosure where an alternative way of ordering is taking place. Despite, a number of different projects pursuing the utopian ideal, such as Paolo Soleri’s Arcosanti [Figure9], Auroville’s sustainability over time was based on the elimination of deviational characteristics within its large and diverse body of inhabitants. Money and religion, as things that led societies to a schism for centuries have been altered as entities capable or connecting rather that separating. The community is exchange based, leaving no use for greed to be accounted. Finally, city’s design promoting an element of sanctity it serves no religion. This may sound paradoxical for some, however, within its given context, the awe aspiring temple serves no god or religion. Rather it introduces a new layer, a blank canvas upon which the individuality of the inhabitants could form multiple new conditions. The unfamiliarity of the form leaves any traces of the known religions in the past, marking the form a container of new intellectual endeavors, rejecting the significance of familiarity in our structured every day. Thus, the unaccustomed architectural form acts as an instigator in perusing an awe-inspiring religion liberation enabling the elimination of diverse characteristics among its residents.

By applying Foucault’s notion of the ship as a heterotopic space to Auroville, it is evident that such spaces operate within layers of meaning. The ship, as is Auroville, act as at a multilayered base of operation, constantly informed and defined by the individual entities it contains. The ship is more than the spatial formation of its entity in the same way that Auroville is constantly informed by the characteristics of its new and old inhabitants. As it happens in a pirate ship, Auroville comes in contrast with the taken for granted mundane idea of ordering that we are familiar with. Power is not imposed within the residence, or pirates, by a commanding principle of power; rather, it is eliminated as a medium of social control, making their enclosure different in a way as it is not dictated by any ruling principles of power. As with any community, both Auroville and the ship have a hierarchy, enabling people to evolve within a preexisting structured community. If one becomes a pirate, then one does not become a captain. In the same way, if one joins Auroville there are certain processes, initiation phases through which one evolves as an integrate member of the community. [Figure 10] The ship is open to infinity while at the same time it acts as a perfect enclosure, contained only by its very own boundaries. It sails around from port to port informing, and more importantly, being informed, by the diversity its very enclosure can provide, in the same way that Auroville does. It may be static but the multicultural body of its inhabitants promote such diversity to occur, as the architecture qualities of the surroundings eliminate any sense of familiar, subconsciously pre-registered space. This symbiotic relationship may not happen through an element of movement but rather through the multicultural circulation of inhabitants, constantly changing and acquainting people; thus, through an element of temporality, turning this futuristic abstract space into place. [Figure 11]

What Can be Seen as ‘Other’

Foucault’s main dispute about power is that, “certain bodies, certain gestures, certain discourses, certain desires come to be identified and constituted as individuals.”[18] Following Barry’s enunciation that the “individual is both an effect of power and the element of its articulation.”[19]

However, through the example of Auroville, the intension was to develop a framework of understanding the element of power through both the perspective of the reader and its inhabitants. Foucault uses the example of the ship as a platform of contention, making us realize how power functions for pirates and how it serves a purpose, “not conceived as a property of possession of a dominant class, state, or sovereign but as a strategy; the effects of domination associated with power arise not from an appropriation and deployment by a subject but from ‘maneuvers, tactics, techniques, functioning’s’; and a relation of power does not constitute an obligation or prohibition imposed upon the ‘powerless’, rather it invests them, is transmitted by and through them.”[20] In his thinking process, he is repeatedly highlighting the importance of the sea in the process of shaping societies over time, as civilizations away from the sea, lacked stimulations in order to maintain the idea of the utopic ‘voyage’, where the civilizations near the sea, did not. In the same way that Auroville’s contrasting inhabitants bring to the community equally diverse characteristics, making it such a unique enclosure formed by people pursuing the same principles by utilizing their individual, extremely diverse, backgrounds.

Foucault, in his text ‘of other spaces’, referees to the ship as “a floating piece of space, a place without a place that exists by itself, that is closed in on itself and at the same time is given over to the infinity of the sea.”[21] Hence, the ship has the ability to “visit different places and at the same time reflect and incorporate them, providing a passage to and through other heterotopias, making it, not by chance, the greatest reserve of the imagination.”[22] That reserve of the imagination acts for Auroville as a tool, as a way of reinventing itself from the small community it could have been to the multicultural cluster it’s still perceiving today, drawing on Hetherington’s approach that “it is how being, acting, thinking or writing differently comes to be seen as Other, and the use to which that otherness is put as a mode of (dis)ordering that is the most significant aspect of heterotopia.”[23]

Unfolding this approach, within the next chapters Auroville will act as a site both marginal and central, associated with sites of social control and the desire for a perfect order. I will try to articulate the ordering processes that took place, as elements mainly based upon a utopic model, aiming for both freedom and social order. Yet “heterotopias are sites of all things displaced, marginal, novel, rejected or ambivalent, acquainting this site of “otherness” with an element of freedom as an aspect of social control.”[24]

Rituals as a Form of Ordering

Through its architecture, Auroville entangles its occupants through a spiritual journey in all three known levels of the world according to ancient Greeks. Its programmatic amplitude enables to experience and interact with the human, to connect with the unreligious divine and reconcile with death, the underworld[Figure 12]. Those three levels, entangled with a layer of architecture, work as an act of reintegration into a new spatial form of alternative ordering, progressively showing people what they truly are and what they are capable of.

“Rituals has been so variously defined-as concept, praxis, process, ideology, yearning, religious experience, function- that it means very little because it can mean so much.”[25] Lined under Kawano’s approach, “rituals mean to become emplaced in a setting as one comes to associate, know and remember it as the site of this ritual.”[26] That is the point when, Auroville, starts to develop the understanding, between its inhabitants and its architecture, “that place, is not fixed or determined, but it can be seen as a site of agency in which ideas can both be contested and contrasted.”[27] In that point Auroville, this heterotopia, “starts to mirror, reflect, represent, designate, speak about all other sites but at the same time suspend, neutralize, invert, contest and contradict those sites.”[28] Thus, Auroville could not, and should not be seen as a finalized structure, a product ready to be consumed, but rather a mean to make sense of and understand our world according to our own needs, appropriating it within the context it provides. As a result, progressively, such sites “acquires the ability to represent both the smallest part of the world and its totality.”[29]

Freedom as an Aspect of Social Control

For many people the concept of an open, horizontally hierarchical community, rejecting the stiff ideas upon our societies are based upon for centuries, like property or religion, comes in contrast with their everyday ordering practices. Foucault refers to it as a condition that ‘draws us out of ourselves’. Thus, Auroville is a disturbing place that alters different degrees of everyday existence. It is a highly heterotopic place with the ability to draw us out of ourselves in peculiar ways. It displays and inaugurates a difference and challenges the space we felt “as home”. Hence, “no pure form of heterotopia can ever exist, but different combinations, each reverberating with all the others.”[30] In a sense, Auroville as such an elaborately designed space indicates that heterotopias do not fully function except in relation to each other. But, “their relationships clash and create further disturbing spatio-temporal units,”[31] confirming Kuma’s approach that “spatial-forms exist only as a phenomenon in the act of reconstruction.”[32]

“He who is subjected to a field of visibility, and who knows it, assumes responsibility for the constraints of power; he makes them play spontaneously upon himself; he inscribes in himself the power relations in which he simultaneously plays both roles; he becomes the principal of his own subjection.”[33] As a result, a place like Auroville is “not liberated from the grip of power, but rather displaced to a secondary and mediatory position by the emergence of a new technology of power, discipline and the production through the exercise of this new form of power of a new reality and knowledge, that of the individual.”[34]

On that account, the effects of power and resistance are intertwined, as freedom for Foucault is an aspect of social control just as social control is implicated in freedom. “Who we are as free subjects comes into being through the effects of power.” For Foucault, “freedom is a condition for the exercise of power.”[35] This paradox of freedom as control and control as freedom is what is defining this heterotopic condition: “no matter how much we wish to be free, we will always create conditions of ordering if not order itself. Equitably, in dividing conditions of social order we will always create positions of freedom from which to resist that order if not freedom from order.”[36]

By using Auroville as a heterotopia however, it would be wrong to privilege either the idea of freedom or control. “It acts as an obligatory point of passage through the prism of today that allow established modes of social ordering to be challenged in ways that might be seen as utopian”[37], such as the lack of money. It would also be wrong to associate this heterotopia just with the marginal and powerless, seeking to articulate a voice that is usually denied them. “An “Other place” can be constituted and used by those who benefit from the existing relations of power within a society, along with the practices associated with it and the meanings developed around it.”[38] Therefore, Auroville acts for the capitalistic society of today as “an obligatory point of passage constituted through different ordering practices that makes visible, if only for a short time, conditions of difference that open up a new perspective on the old order and all its faults.”[39]

Auroville as a Place for “Doing Nothing”

In his introduction of the book “Violence” the Slovenian Philosopher Slavoj Zizek uses an example given by Jean-Paul Sartre in his book “Existentialism and Humanism”. In that book, he writes “about a young French man’s dilemma during the Second World War as he is torn between entering the Resistance or helping his ill mother. In fact, in front of this choice without any a priori answer, Zizek proposes a third pill. This third proposition is to withdraw to a secluded place in order to work and analyze the situation from outside of it.”[40] “Following Žižek’s remarks, the global condition of nowadays cannot orient towards any concrete political attitude: the most appropriate action in order to undertake a political responsibility would be to do nothing.”[41] Zizek proposes that this “withdrawal to a “secluded place” would serve in order to “wait and see” the evolution of today’s condition, performing at the same time a systematic patient critical analysis.”[42]

Auroville then, could be fully integrated within Zizek’s notion of a “secluded place”. If Zizek’s “secluded place” marks the unfeasibility of the notion of waving todays temporality then Auroville acts as the implementation of that exact notion. The inhabitant of Auroville could then be seen as “a hero of the global challenging himself in concepts of political responsibility.”[43] Auroville itself “is supposed to be a responsible device but it may already introduce to a new concept of responsibility while in the same time it gives a perspective towards an idiosyncratic notion of irresponsibility. It is after all a project of self criticism.”[44]

“In ancient greek “Thought” [skepsis] meant supervision, contemplation. And it’s the same today: exterior world determines the major part of our thinking structure.”[45] Following that logic, we can assumingly suggest that Zizek’s house hold the characteristics of a place of otherness, a “common place”. As a result, by applying this logic towards the formation of a community such Auroville, the austere denial of what could be seen today as common is apparent. “It is a difficult place for responsibility, the experience of which is already done in the ruined fields of our old “living” cities.”[46]

However, the fascinating characteristic of Auroville’s architecture is its ability to interpret movement and transparent elements in a physical form. “The residence can construct the most valuable interior while it organizes a public space. They can be taken as a particular screen that exposes in public what it shelters.”[47] “The line between public and private no longer coincides with the outer limit of a building.”[48] That transformation to some extent, blurs the boundaries between the interior and exterior qualities of each contained space, “transforming this new interiority to the most untouchable spectacle.”[49][Figure14]

Conclusion:

Over the centuries, most utopic communities failed to acknowledge the most important aspect behind their own formation. The element and the significance of the individual within an organized group of people, enabling the necessary diversion for human stimulation to occur. “If we have no connection whatsoever with the world beyond the one we take for granted, then we run the risk of drying up inside. If all the people in our inner circle resemble us, it means we are surrounded by our mirror image. Our imagination might shrink.[50]”

Auroville was chosen as a case study as it was the only utopian community of such scale that was designed from the beginning as the ultimate manifestation of the utopic place, as perceived from the prism of renown scholars such as Michel Foucault. If we look at Auroville however as the sum of absolute numbers and facts, it failed to fulfil its programmatic functions of creating a 20,000 people community as, such endeavors presuppose a direct schism with the past, something not many people are yet still to undertake. Such communities always possessed elements of deviational characteristics as for some they could be seen as the ultimate manifestation of the utopic space, where for others, a dystopic reality. A new spatial configuration that presupposes degrees of freedom the western world is currently lacking. [ Figure 10] Thus, in seeking the true capacity of the heterotopia as a place of alternative ordering, Auroville provides an ironic look of yesterday in the resemblance of today, making its community a social cluster that refuses to engage in the pursuit of the original as this presupposes an idyllic time in the past which the present is now separated from and is attempting to recapture.

Bibliography

· Antonas, Aristeides. ‘Archipelago of protocols’. Barcelona: DPR-Barcelona. 2016.

· Beatriz, Colomina. ‘Skinless Architecture’. Florida International University Press. 2008.

· Blauvelt, Andrew, Greg Castillo, and Esther Choi. Hippie modernism the struggle for utopia. Minneapolis: Walker Art Center. 2015.

· Bina, Bhatia. Auroville: A Utopian Paradox. NY: Columbia University Academic Commons, 2014.

· Cook, Peter. ‘The Future of Architecture Lies in the Brain in Experimental Architecture’. New York: Universe. 1970. p. 133-153.

· Deamer, Peggy. ‘Architecture and Capitalism’. Routledge, New York. 2014.

· Dehaene, Michiel and Lieven, De Cauter. ‘Heterotopia and the City: Public Space in a Postcivil Society’. London: Routledge. 2008.

· Delaney, Joseph. ‘Ritual space in the Canadian Museum of Civilization: consuming Canadian identity’, London: Routledge. 1992.

· Dorn, James. “Equality, Justice, and Freedom: A Constitutional Perspective.” Cato Journal, 2014, vol. 34, issue 3.

· Doxiades, Konstantinos. ‘Ekistics: an introduction to the science of human settlements’. London: Hutchinson, 1969.

· Elias, Norbert. ‘The Court Society’. Volume 1, The History of Manners. Oxford: Blackwell. 1983.

· Foucault, Michel. “Of Other Spaces”, translated by Jay Miskowiec, Architecture/Mouvement/Continuité, 1984.

· Foucault, Michel. ‘The Order of Things’, London: Tavistock/Routledge, 1989.

· Foucault, Michel. ‘Different Spaces’. London: Allen Lane. 1998.

· Foucault, Michel. ‘History and Madness’, London: Routledge. 2006.

· Foucault, Michel. ‘Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison’. Allen Lane, Penguin Press: London. 1977.

· Foucault, Michel. ‘The Subject and Power’. Michel Foucault:Beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics, Brighton: Harvester Press.

· Foucault,Michel. ‘Space, knowledge, and power’.The Foucault Reader, Harmondsworth: Penguin. 1986.

· Foucault, Michel. ‘The History of Sexuality’. Allen Lane, Penguin Press: London. 1979.

· Gillian, Rose. Feminism and Geography, Oxford: Polity Press, 1993.

· Hailey, Charlie. ‘Camps: a guide to 21st-century space’. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 2009.

· Hetherington, Kevin. The badlands of modernity: heterotopia and social ordering. London: Routledge, 2006.

· Kuma, Kengo. ‘Dissolution of Objects and Evasion of the City’. Japan Architect, Vol 38 (summer). 2000.

· Kundoo, Anupama. ‘Auroville: An Architectural Laboratory.’ Architectural Design 77.6 (2007): p.50-55.

· Kawano, Shuichi. ‘Ritual Practice in Modern Japan- Ordering People, Place and Action’. Honolulu: University of Hawai’I Press. 2005.

· Lefebvre, Henry. ‘The Production of Space’. Oxford: Blackwell. 1991.

· Lefebvre, Henry. ‘The Urban Revolution’. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis. 2003.

· Mandeen, John. ‘Auroville architecture: towards new forms for a new consciousness. Auroville’. Tamil Nadu, India: Prisma, 2014.

· Nails, Debra. "Socrates." Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. 2005.

· Said, Edward. ‘Culture and Imperialism’. London: Vintage. 1994.

· Shields, Rob. ‘Places on the Margin’. London: Routledge, 1991.

· Simmel, Georg. “The Metropolis and Mental Life” (1903), from On Individuality and Social Forms, ed. Donald N. Levine, University of Chicago. 1971. p. 324–39.

· Sloterdijk, Peter. ‘In the world interior of capital: towards a philosophical theory of globalization’. Cambridge: John Wiley & Sons. 2013.

· Smart, Barry. ‘Michel Foucault’, Ellis Horwood, Tavistock: London. 1985.

· Soja, Eduard. ‘Heteropologies: a remembrance of other spaces in Citadel-LA’. London: Verso, 1990.

· Soleri, Paolo. ‘Arcology: the city in the image of man’. Phoenix: Cosanti Press. 2006.

· Stallybrass, Peter and Allon White. ‘The Politics and Poetics of Transgression’. London: Methuen. 1986.

· Tonkins, Frances. ‘Space, the City and Social Theory’. Cambridge: Polity Press. 2005.

· Turner, Victor Witter. ‘The anthropology of performance’. New York: PAJ Publications. 1988.

· Turner, Victor Witter .’ The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-structure’. Aldine Transaction. 2007.

· Žižek, Slavoj. ‘Violence: six sideways reflections’. London: Profile Books. 2009.

Online Bibliography

· HETEROTOPIC ARCHITECTURES /// Zizek Residence by Aristide Antonas (in dialogue with dpr-barcelona)." THE FUNAMBULIST MAGAZINE. July 01, 2011. https://thefunambulist.net/architectural-projects/heterotopic-architectures-zizek-residence-by-aristide-antonas-in-dialogue-with-dpr-barcelona-2.

· "A House for Doing Nothing | Political Attitudes from Secluded Places." Dpr-barcelona. July 01, 2011. https://dprbcn.wordpress.com/2011/07/01/zizek-house/.

· TEDtalksDirector. "Elif Shafak: The politics of fiction." YouTube. July 19, 2010. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zq7QPnqLoUk.

[1] Dorn, James. “Equality, Justice, and Freedom: A Constitutional Perspective.” Cato Journal, 2014, vol. 34, issue 3, p. 497.

[2] Bina, Bhatia. Auroville: A Utopian Paradox. NY: Columbia University Academic Commons, 2014. p.27

[3] Foucault, Michel. “Of Other Spaces”, translated by Jay Miskowiec, Architecture/Mouvement/Continuité, 1984.

[4] Hetherington, Kevin. The badlands of modernity: heterotopia and social ordering. London: Routledge, 2006. p.41.

[5] Gillian, Rose. Feminism and Geography, Oxford: Polity Press, 1993. p.49.

[6] Soja, Eduard. ‘Heteropologies: a remembrance of other spaces in Citadel-LA’. London: Verso, 1990. p.17.

[7] Shields, Rob. ‘Places on the Margin’. London: Routledge, 1991. p.103.

[8] Delaney, Joseph. ‘Ritual space in the Canadian Museum of Civilization: consuming Canadian identity’, London: Routledge, 1992, p.53.

[9] Lefebvre, Henry. ‘The Production of Space’. Oxford: Blackwell. 1991. p.19.

[10] Foucault, Michel. ‘The Order of Things’, London: Tavistock/Routledge, 1989.

[11] Nails, Debra. "Socrates." Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. 2005. p. 9.

[12] Ibid. p. 15.

[13] Stallybrass, Peter and Allon White. ‘The Politics and Poetics of Transgression’. London: Methuen, 1986, p.18.

[14] Doxiades, Konstantinos. ‘Ekistics: an introduction to the science of human settlements’. London: Hutchinson, 1969. p. 69.

[15] ibid.p.27.

[16] Bina, Bhatia. ‘Auroville: A Utopian Paradox.’ NY: Columbia University Academic Commons, 2014. p.9.

[17] Mandeen, John. ‘Auroville architecture: towards new forms for a new consciousness. Auroville’. Tamil Nadu, India: Prisma, 2014. p.7

[18]Foucault, Michel. ‘Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison’. Allen Lane, Penguin Press: London. 1977. p.98.

[19] Smart, Barry. ‘Michel Foucault’, Ellis Horwood, Tavistock: London. 1985. p.79.

[20] Foucault, Michel. ‘The History of Sexuality’. Allen Lane, Penguin Press: London. 1979. p.93.

[21] Foucault, Michel. ‘Of Other Spaces’. translated by Jay Miskowiec, Architecture/Mouvement/Continuité, 1984.

[22] Foucault, Michel. ‘Different Spaces’. London: Allen Lane. 1998. p.186.

[23] Hetherington, Kevin. The badlands of modernity: heterotopia and social ordering. London: Routledge, 2006. p.51

[24] Foucault,Michel. ‘Space, knowledge, and power’.The Foucault Reader, Harmondsworth: Penguin,1986, p.237

[25] Turner, Victor Witter. ‘The anthropology of performance’. New York: PAJ Publications. 1988. p.10.

[26] Kawano, Shuichi. ‘Ritual Practice in Modern Japan- Ordering People, Place and Action’. Honolulu: University of Hawai’ Press. 2005. p.8.

[27] Tonkins, Frances. ‘Space, the City and Social Theory’. Cambridge: Polity Press. 2005, p.7.

[28] Foucault, Michel. ‘Different Spaces’. London: Allen Lane. 1998. p.182.

[29] ibid. p.179.

[30] Dehaene, Michiel and Lieven, De Cauter. ‘Heterotopia and the City: Public Space in a Postcivil Society’. London: Routledge, 2008. p. 22.

[31] Foucault, Michel. ‘History and Madness’, London: Routledge, 2006, p.362.

[32] Kuma, Kengo. ‘Dissolution of Objects and Evasion of the City’. Japan Architect, Vol 38 (summer), 2000. p.58.

[33]Foucault, Michel. ‘Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison’. Allen Lane. Penguin Press: London. 1977, p.202-203.

[34] Smart, Barry. ‘Michel Foucault’, Ellis Horwood, Tavistock: London. 1985. p.81.

[35] Foucault, Michel. ‘The Subject and Power’. Michel Foucault:Beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics, Brighton: Harvester Press, p.221.

[36] Hetherington, K. ‘The Badlands of Modernity: Heterotopia and Social Ordering,’ London: Routledge, 1997,p.52-53.

[37] Ibid. p.57.

[38] Ibid. p.52.

[39] Elias, Norbert. ‘The Court Society’. Volume 1, The History of Manners. Oxford: Blackwell. 1983.

[40] HETEROTOPIC ARCHITECTURES /// Zizek Residence by Aristide Antonas (in dialogue with dpr-barcelona)." THE FUNAMBULIST MAGAZINE. July 01, 2011. https://thefunambulist.net/architectural-projects/heterotopic-architectures-zizek-residence-by-aristide-antonas-in-dialogue-with-dpr-barcelona-2.

[41] "A House for Doing Nothing | Political Attitudes from Secluded Places." Dpr-barcelona. July 01, 2011. https://dprbcn.wordpress.com/2011/07/01/zizek-house/.

[42] Žižek, Slavoj. ‘Violence: six sideways reflections’. London: Profile Books. 2009. p. 33.

[43] Antonas, Aristeides. ‘Archipelago of protocols’. Barcelona: DPR-Barcelona. 2016. p.71.

[44] Ibid. p.27.

[45] "A House for Doing Nothing | Political Attitudes from Secluded Places." Dpr-barcelona. July 01, 2011. https://dprbcn.wordpress.com/2011/07/01/zizek-house/.

[46] Antonas, Aristeides. ‘Archipelago of protocols’. Barcelona: DPR-Barcelona. 2016. p.55.

[47] Beatriz, Colomina. ‘Skinless Architecture’. Florida International University Press. 2008. p. 31.

[48] ibid. p. 11.

[49] Žižek, Slavoj. ‘Violence: six sideways reflections’. London: Profile Books. 2009. p. 19.

[50] TEDtalksDirector. "Elif Shafak: The politics of fiction." YouTube. July 19, 2010. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zq7QPnqLoUk.