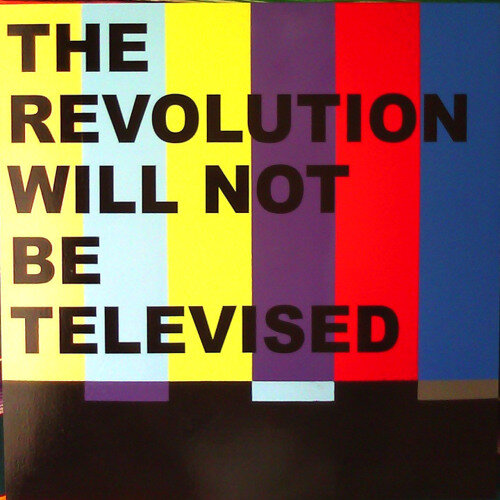

The Revolution Won’t be Televised

Architecture is both an art and a science discipline, resembling many aspects of our lives, constantly evolving to the existing circumstances of each era. In parallel, social media is a mean through which, political, cultural and economic aspects of a community are contested and contrasted and, for a big part of our society, form the basis of any communication process.[1] They both operate alongside, as the product we perceive today as architecture, emerges from the narratives established through social media. The ability of such mediums to inform the common belief, is something unquestioned, however, their capacity to manipulate an argument through a mechanism of hierarchy, will act as a catalyst in understanding not just the nature of the information, but the process through which social media become a valuable tool in the formation and transmission of a specific agenda.

Within this essay, I will try to explore the capacity of architecture to be part of a social media agenda, and if the way through which it is conveyed could render it as an ‘object’ of significance, or debate to some extent, and increase the public interest towards it. Instigating a mechanism of social interaction which could elevate architecture in a political agenda, via the ramification of the image as a way of producing architecture.

For someone to fully understand and utilize this essay as a framework in understanding the importance and power of architecture, it is imperative to recognize the capacity of architecture, more than any other art or science, to project the symbolic values which it serves. Space has always served as an action of expression. We spent all our lives in buildings and our thinking is informed and developed within them. From the master planning of a city to the architecture characteristics of a house, space has always followed the needs and desires of a society, taking into consideration, geography, time, social and political conditions and cultural beliefs.

Initially, architecture and social media might seem like two completely different branches, not sharing any common ground. The distance between them however, is not that great, as social media constitute a sector which informs every individual separately, and involves all the social, political and economical structures a place. Likewise, architecture comes into existence, when it is produced in alignment with such aspects. Thus, architecture and social media could, for some, create a new typology. An in-between space between our physical world and the virtual place that social media occupy. If one of the core reasons of our happiness, our negative feelings, our personalities are reflections of the qualities of spaces we encounter[2], social media has changed the way we perceive such structures as something more than a non-dynamic static object, unable to adopt to the demanding circumstances of the moment.

We see a beautiful building, or a beautiful street and we upload it into a virtual space. The capacity of such action goes beyond just the transmission of a single image to a larger audience.[3] We are fragmenting architecture, disregarding its core notion of a coherent narrative.[4] That fragmentation of our physical world into our virtual one, is denying architectures potential, sometimes, to convey the very own message of its significance. Digital tools changed the way through which pictures are created. Not only the medium through which we used to edit them changed, but the extent to which we can alter the very own nature of the image in the first place. Thus, the beatification of the image as an individual part in a loosely defined virtual space is altering, or ever corrupting, the narrative of the very object it depicts. As a result, spatial qualities, many times struggle to distinguish themselves from their own reproductions.[5]

Social media then, could and should not be seen as a threat for architecture, but rather an “essential component of the concept of modernity. The idea of a future toward which we travel after a radical rupture with the past.”[6] That exposure of not only the visual, but the very own nature of the discipline is a great opportunity to fully fathom the elongation of architecture and thus comprehend it could “no longer be contained within the scope of a single discipline.”[7] If we truly want to explore beyond the perceived methodologies of the present, we have to take into consideration the very own diverse nature of our “products”. Buildings and architectural interventions are not static objects. Rather they endlessly evolve in a constant transformation, reshaping their very own “identity” from objects of facts to objects of concern. And social media, if utilized properly, provide the ideal framework for exactly that.

The power of social media is immense and can contribute in the simulation of a space or a place and subsequently to its transmission to an audience that would otherwise never experience it. Many would argue that the lack of that very own physicality lessens the experience of such places. Even if that’s the case, no one could reject the establishing interest that such stimulation produce, engaging more people with the discipline of architecture. From the paper projects of the 60’s, intended to raise social concern, to the biodegradable mushroom bricks of the present, architecture always had a radical agenda, but failed to contextualize it beyond its very own strictly defined walls. Thus, even through the partial exposure of the story, our field could gain a wider collective contribution of the people in reimagining the city. Setting our discussion, within a larger audience, contesting and contrasting not only the built environment, but more importantly, the unbuilt within we live in.

[1] Dearing, J. and Rogers, E. (1996). Agenda-setting. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, p.93.

[2] Yick, N. (2018). The Importance of Architecture. [online] The Odyssey Online. Available at: https://www.theodysseyonline.com/importance-architecture [Accessed 18 Nov. 2018].

[3] Colomina, Beatriz. 2001. "Enclosed by Images: The Eameses' Multimedia

Environments." Grey Room (2): 19

[4] Lefebvre, H. and Nicholson-Smith, D. (2011). The production of space. Malden, Mass: Blackwell, p.47.

[5] Foucault, M. “Of Other Spaces”, translated by Jay Miskowiec, Architecture/Mouvement/Continuité, 1984.

[6] B. Latour, “Fifty Shades of Green” in Environmental Humanities 7 (2015): 221.

[7] E. da Costa-Meyer. “Architectural History in the Anthropocene: Towards Methodology” in The Journal